Even as a child, Ron Joyce knew he was poor and didn’t want to stay that way.

One day, his friend Jack Coulter had heard enough of it.

“I said, ‘Well, we’re all poor,’” Coulter remembered Friday.

“There were only two families in Tatamagouche then that had any money. The rest of us were well fed and were warm in the winter — we just never had anything much else to speak of.”

Joyce died Thursday at his home in Burlington, Ont., with his family at his side. He was 88.

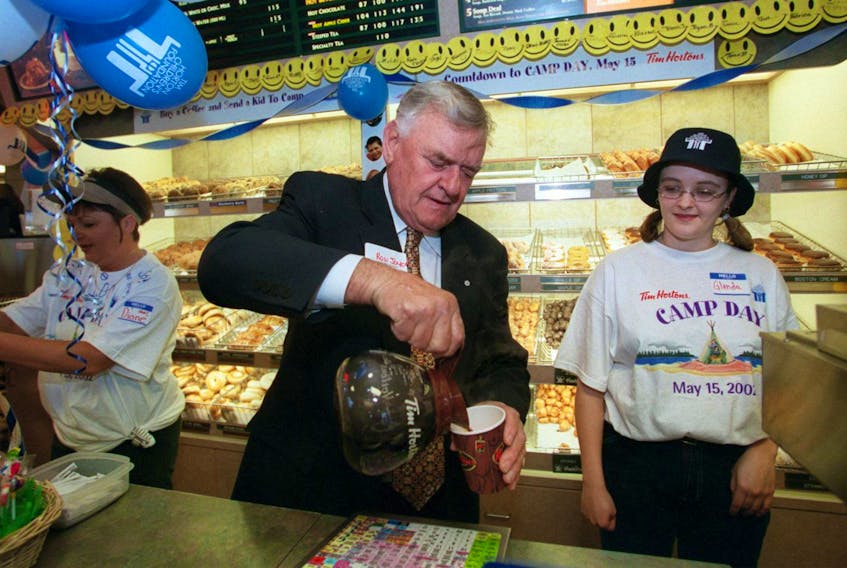

To most Canadians, Joyce will be remembered as the intrepid former police officer who joined with hockey player Tim Horton to build an iconic chain of coffee shops that now has over 4,000 outlets.

He was also a philanthropist, who as of 2017 had given $52 million to universities and colleges in Atlantic Canada alone.

Then there are the thousands of children who likely don’t know Joyce was behind the network of seven camps for underprivileged children located between Tatamagouche, Alberta and Kentucky.

For Coulter, he’ll just be an old friend.

A friend that left Tatamagouche for Ontario to make a new life at 15 years old, serving first in the navy as a wireless operator and then nine years as a police officer in Hamilton.

On one particularly memorable call with the police force, he helped deliver a baby.

During his early years in Hamilton, the old friends in Tatamagouche didn’t hear much from Ron.

To be fair, he was rather busy.

Tim's king was once Dairy Queen man

Turning toward private business, he bought a Dairy Queen and wanted to add another but couldn’t get financing. That’s when he teamed up with Horton, the Toronto Maple Leafs defenceman who with another businessman had started a chain of coffee shops.

So now he was a cop who was also learning to make doughnuts.

In 1974, with the franchise 40 outlets strong, Horton died in car accident and Joyce bought out his widow for $1 million.

He sold Tim Hortons to Wendy’s International Inc. in 1996. It was later purchased by Burger King, and the two brands became Restaurant Brands International in 2014.

Despite the overall success of Tim Hortons, however, Joyce did not want to see one of his restaurants interfere with small-business interests in his home village and vowed there would never be a franchise in Tatamagouche.

“I heard that long ago, that there would never be a Tim Hortons in Tatamagouche as long as he lived,” said Mike Gregory, Colchester County councillor for the Tatamagouche area.

“He was a pretty generous guy, there was no doubt about it. He never forgot his roots, never forgot where he came from.”

A statement from Tim Hortons said: “Ron was a larger-than-life friend who not only helped create one of Canada’s most iconic brands but was passionate about ensuring Tim Hortons always gave back to the community.”

“He was always careful to give credit to Horton and his other business partner, Jimmy Charade,” said Douglas Hunter, who has written both the history of the franchise and about the life of its founder in the books Open Ice and Double Double.

“But there’s little doubt Joyce was the guy with the real ambition. If Horton hadn’t have died in the car accident, he would have stayed involved in hockey, maybe as a general manager eventually. Joyce was about the coffee and the doughnuts.”

While Coulter knew Joyce as a boy, Hunter knew him as a prominent businessman and a powerful force.

Author says Joyce 'proud of what he’d accomplished'

The nature of the man behind the reputation he came to know better after the interviews, when he was waiting for Open Ice to go to print.

Someone at the book’s publisher, Penguin, thought that more copies could be sold if it was by the cash at Tim Hortons restaurants across Canada. So, without asking the author, they sent a copy of the as-yet-unpublished manuscript to corporate office at Tim Hortons.

“I was mortified,” Hunter said.

Among the people quoted in Open Ice was Lori Horton, Tim’s widow, who was at the time suing Joyce over the settlement reached two decades earlier.

Also in the book were details about how during the business’ early days to keep things going, Joyce had mortgaged properties he didn’t even own.

There were also details about Horton’s drinking.

It was a book by a professional journalist, not a hagiography.

Hunter got a call from Joyce out of the blue on a Thursday.

“He said, ‘Yeah, I’ve got it, going to give it a read-over. Don’t worry, I’m not going to want to change anything,’” Hunter said.

“Then he phoned again, in a bit of a sweat, suddenly it was, ‘Boy, I didn’t know that tape was running.’

Then Hunter, a freelance journalist with no resources for a protracted legal fight, got nervous.

“He could have crushed me,” said Hunter.

“I said, ‘Ron, do this for me - take the weekend and read the whole thing.’ Monday the phone rings. He said, ‘I read it, I’m not happy with everything but I understand why it’s there.’”

And over what likely would have been the objections of his corporate lawyers, Joyce told Hunter to run the book.

To Hunter, that said a lot about the man he was dealing with.

Later, he’d get phone calls out of the blue from Joyce, just to chat.

“He was proud of what he’d accomplished,” Hunter said.

“He wasn’t boastful or anything, he just liked that it had happened.”

Back to Tatamagouche

Though he wanted to escape his youthful poverty, Joyce never wanted to leave Tatamagouche behind.

He founded the Fox Harb’r Golf Resort and Spa near Wallace, Cumberland County, and placed one his children’s camps on the outskirts of Tatamagouche.

He also was quietly generous in the community.

“If there were people he heard about in the community who needed help, he would do it in a quiet way,” said Ron Creighton, a lawyer with Truro firm Patterson Law who lives in Tatamagouche.

“The schools too. I know one day not too long ago he called the principal there and said ‘What can we do to help the school?’”

Later in life, Joyce’s old ties to home became more pronounced.

Coulter started getting more regular phone calls, just to chat about growing up and the ailments of growing old.

“He was a good guy,” said Coulter, 89. “I’m sorry to hear that he’s gone.”

“My father had a big vision and a big heart,” Steven Joyce said in a statement on behalf of the family. “Through hard work, determination and drive, he built one of the most successful restaurant chains in Canada.

“He never forgot his humble beginnings.”

Premier Stephen McNeil said he was saddened to hear of Joyce’s passing.

“From a small community in Nova Scotia, he went on to co-found an iconic Canadian business,” McNeil said in a statement. “His generosity was also well-known and made a difference in the lives of many.

“I offer my condolences to his family and all those who cared about him.”

With files from Harry Sullivan and Steve Bruce

I said this just the other day. My mother is a Joyce from Westville, NS. Ron Joyce was a relative, like many Joyces from Pictou County. #timhortons #ronjoyce

— Michael de Adder (@deAdder) February 1, 2019

Played 18 holes w/ #RonJoyce @ FoxHarbr'

— Ian Andrew (@IanAndrewGolf) February 1, 2019

Found him to be a complicated man.

I loved what he accomplished w/ #TimHortons #ChildrensFoundation

That is the legacy that matters most. pic.twitter.com/tZmVU1Xq07