The 11 great white sharks tagged in Nova Scotia waters this past fall are starting to provide a wealth of scientific data, not the least of which is their satellite-tracked migration pattern.

Much like Canadians who pack their bags for Florida to avoid the winter, these snowbird sharks have all been detected in southeastern U.S. waters.

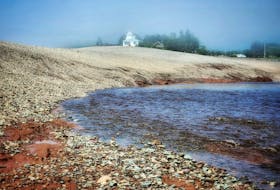

The U.S.-based research organization Ocearch conducted a successful expedition in late September and early October off Cape Breton's Scaterie Island and the South Shore's West Ironbound Island not far from Lunenburg, They captured, sampled and affixed tracking tags to the big predators before releasing them back into the Atlantic. This followed a similar expedition that did the same for six sharks from the Lunenburg-area waters in the fall of 2018.

The satellite-tracking-enabled tags send a signal every time the dorsal fins break the surface long enough to make contact with the system and the sharks' positions are then shared on Ocearch's website for fans of the big beasts to see. They also maintain social media accounts associated with the sharks to facilitate ongoing engagement.

"We're thrilled that all 11 sharks from our Nova Scotia expedition are pinging in," Ocearch founder Chris Fischer said in a telephone interview.

"There's just so much data, it's unbelievable. It's hard to even keep your head around so many sharks that are moving so much."

One of the prize tracks belongs to a huge female white shark that Ocearch named Unama'ki. Measuring about 4.75 metres in length and estimated to weigh more than 940 kilograms, Unama'ki was tagged off Scaterie Island and named in honour of the Mi'kmaw people.

"Unama'ki is particularly interesting because she's a large, mature adult female and she has the potential of showing us where the Canadian white shark gives birth," Fischer said. "And she has wrapped all the way around Key West into the Gulf of Mexico and almost back up as far north as just west offshore of Tampa."

That's different than the rest of the Nova Scotian sharks that are all aggregating in a stretch of the U.S. southeastern Atlantic coast from just south of Cape Hatteras, N.C., all the way down to around Cape Canaveral, Fla. Fischer called the area the North Atlantic Shared Foraging Area, or NASFA.

If she is pregnant, Unama'ki will follow a two-year migration route, different from that of the males, who stick to a one-year migratory path. Fischer said it will be very interesting to see if she, and Luna from the 2018 expedition, take a different route next fall, which would lead to a lot of interest in where they go in the spring of 2021.

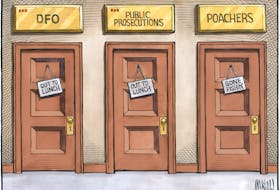

Ocearch is also preparing the first round of scientific reports that will be sent to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans next week based on the initial observations.

"From a reproductive standpoint, we're still not seeing any clear evidence of mating scars on the females to indicate that mating is occurring there," Fischer said. "We did get semen from three white sharks up there. Their semen didn't look like they were particularly ready to mate even though it felt like that they were rutted up and ready to mate, so we're not quite sure we understand what that means. It doesn't mean they're not mating up there, we're just still in the midst of collecting data and we've had a lot of new data to come from this last one."

Ultrasound scans on the sharks revealed none of the females were pregnant but also led to the first recorded scan of great white hearts in action.

"This heart rate thing is interesting," Fischer said. "You know, we got four heart rates through our ultrasound machine and a full heart inspection of these white sharks for the first time. Seems like their average resting heart rate is around 10 beats per minute, which is extremely slow. That's kind of like the beginning of a whole new journey of science."

Chemical analysis has revealed very high levels of mercury in the sharks' flesh, he said, something to be expected in an apex predator as the process of bio-accumulation brings in the contaminants of everything they eat in their position at the top of the food chain.

"They're averaging about 10 times higher than what is recommended for human consumption," Fischer said. "So, obviously, no one should ever be eating any white shark meat.

Fecal samples from the sharks are being tested for microplastics and already reveal the expected presence of seal fur.

Bacterial samples are being tested for antibiotic capabilities against eight human and four marine pathogens, he said, with the objective to find new drugs to fight infections in people.

A big surprise was the presence of juveniles in the 2.5- to 2.7-metre-long range besides the expected sub-adults and fully mature sharks, he said.

"To see some of these smaller juveniles just means there's just a whole lot more going on up there than we anticipated," Fischer said. "Many sizes, many sexes, many different stages of life, which I think is going to be a big part of what we're going to try to work on in the next few years.

"It's clear now there's just a whole other area of work to be done. Now, we have so many spots based on the tracking of the 2018 sharks and now the 2019 sharks that ... there are so many places to go to continue learning that it's hard to pick where to go next. And our problem used to be that we didn't know where to go. That's a big change. That's a huge change."

Ocearch is preparing to come to Canada to meet with DFO scientists and representatives with the hopes of collaborating on a multi-year plan for further research.

Fischer is also hoping more Canadian scientists can get involved and is open to researchers contacting Ocearch to see what can be arranged.

"Everyone is invited," Fischer said. "This is a journey to try to make sure that our kids can eat food. So there's no time for these individual agendas or silly silos. We just have to get as many of the bright people we can get together who want to serve the future with the right capacity and the ship and the ability to deliver them what they have to have to learn, which is safe access to these animals. There's no more time for these silly individual agendas, so we invite everyone all the time, because we're in it for our grandkids and we hope that other people are, too."