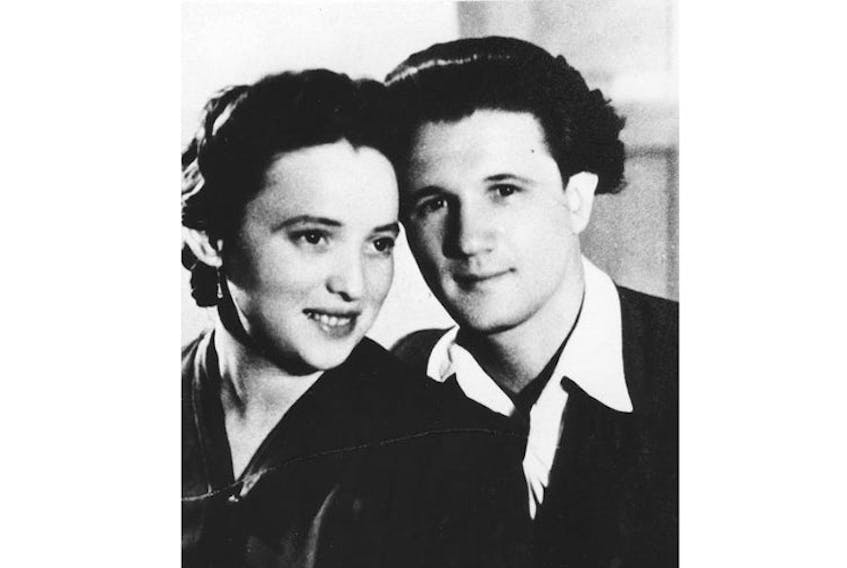

They met while trying to locate lost family members. What they found instead was each other.

Anna Zuckerman and Hershel Blufarb had visited the same displaced persons camp following the chaos of the Second World War. They were both the only known members of their immediate families to have survived.

As a young boy growing up in North Sydney, Fred Blufarb said his parents talked about their remarkable Holocaust escapes with some regularity. It was his mother, however, who was most forthcoming about the tale.

Fred Blufarb

Fred Blufarb“Sometimes she’d directly engage you and she was very focused,” said Blufarb, who runs a second-hand store near the Marine Atlantic ferry terminal to Newfoundland and Labrador.

“And other times, she would kind of drift off as if she was seeing it or replaying it like a movie. Sometimes she’d be just calm and sometimes she’d be emotional about it.”

ANNA'S STORY

Fred’s mother, Anna, grew up in an upper-middle class home surrounded by fine furnishings. The Polish girl’s life would be forever changed around age 16.

At the outset of the war, there were 14,000 Jewish people living in the former city of Tarnopol, Poland. By mid-March 1943, only about 700 Jews remained by official count, but several hundred others were believed to be in hiding.

Nazi leader Adolf Hitler had begun bombarding Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, by sending some 1.5 million troops in what he referred to as a defensive action.

Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany, initiating the Second World War.

German forces began their terror by looting the homes of wealthy families such as the Zuckermans.

Anna’s family, along with many others, would be sent into a cordoned-off section of the city, where they lived in fear of persecution and death.

The biggest help to Anna’s survival came in the form of a written pass. It was given to her by a German officer whose wife was helped by Anna’s father, a local healer and barber.

“If there was an action coming she would say I’ve got a ‘Get out of jail free card,’ and she was able to get out,” said Blufarb.

“Other times, I think she may have escaped through fences.”

In total, Anna had endured 18 killings over a two-year period but she was not immune to the widespread pain and suffering. She witnessed unthinkable atrocities, none more painful than hearing her father say his goodbyes as he was led outside an apartment by German officers.

Herman Zuckerman would later be found shot dead in a marsh.

Anna also recalled seeing a large crop of what her son believes was cabbage that grew atop a mass grave. Despite widespread hunger, no one in the city wanted to eat the plump vegetables as they bore a reddish hue when sliced open.

“That was one of her most prominent stories,” Blufarb said. “She really wanted to drive that one home – that this happened, this atrocity – the oversized cabbage and the red colours on the inside.”

“And I think maybe that’s why God let me live, so I can tell this story.”

Anna would eventually by saved through her own skill and trickery.

She had learned to impersonate a Ukrainian woman so well, that instead of being shot or sent to a concentration camp, she was sent for two years to what her son believes was a forced labour camp in Germany.

In 1945, Anna was liberated. It was a mix of emotion, said her son, as she and many others would suffer from survivor’s guilt.

In an interview before her 1999 death, Anna spoke to Cape Breton’s Magazine about her harrowing tale.

“Survivors are not so many left,” she said.

“And nobody knows how long you’ll have them around to tell the story … I think I have to tell the story. So it won’t be said it never happened.

“That’s what hurt the most, when people tell you it couldn’t be, it never happened. And here, I lived through it.

“And I think maybe that’s why God let me live, so I can tell this story.”

HERSHEL’S STORY

As Germany invaded Poland, many Jewish men had decided to flee on foot or by freight-hopping.

As a result of Hershel’s daring adventure, Fred Blufarb and his brother Benjamin have an older half-sibling, Vladimir, who grew up in Russia.

“You really, really, really had to live by your wits,” said Blufarb of his father’s escape at age 17.

Among the memories Hershel once shared with his son was hiding in tall vegetation as low-flying German planes flew by on strafing runs.

Hershel told his son about the importance of not wearing white as it could be spotted from above.

“It would be nothing for everybody to jump in the grass and lay down for cover and he would get up and the guy next to him wouldn’t,” said Blufarb.

“I remember my dad basically saying … it’s like you were hunted, and if you were Jewish you were going to be exterminated.”

In order to fight starvation, Blufarb said his father was once forced to consume the meat of a dead horse.

Blufarb said both of his parents would talk about anxieties that were experienced during bombings. Both Hershel and Anna heavily relied on their gut feelings.

And in one particular incident, Hershel’s intuition saved his life.

“He got out of the building and a few moments later that building got hit,” said Blufarb.

“He always wondered, ‘why did God save me?”’

A NEW LIFE

For a time after the war, the Blufarbs lived in both Israel and England.

They arrived on Canadian soil Jan. 10, 1952.

Their son believes they landed at Pier 21 in Halifax and soon after, situated themselves in Montreal, before moving on to Newfoundland and eventually settling in North Sydney.

They provided their sons with loving childhoods, but Blufarb said they were overprotective parents.

“They say forgive and forget,” he said. “I don’t think that took place for either of my parents but they didn’t live their lives filled with contempt for those that hated them.

“They embraced life and lived life and raised their family with love and caring because if you harboured that contempt you wouldn’t have been able to provide a loving environment for your own family. They never taught us to hate because they were the recipients of hate so what would that give back? Nothing.”

Hershel Blufarb passed away in 1992. Anna died in 1999.

Before her death, Anna was one of 50,000 survivors to share testimony to the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education, founded by American filmmaker Steven Spielberg.